Maternal brands – how deep is the love?

Andrex – part of my life since 1967. Image courtesy of Mezhopking

My father recently bought a new car and almost immediately ran the battery down because he left the hazard warning lights on all night.

Anyway, he was telling me this story when suddenly he said he had sorted the problem by calling the RAC out. He might as well have told me that he was sleeping with a woman that was not my mother.

The RAC! That is not how we were brought up! We were an AA family, always have been, always will be. I was shattered. What next? Swinging? Gun crime? Voting Tory?

The AA is what I call a maternal brand. I was brought up with it and like my other maternal brands I find it familiar and comforting.

And alongside Persil, Fairy Liquid, Andrex, Anchor butter and Heinz tomato ketchup, I choose it without consideration of the alternatives and without substitution.

Having the keys to a brand, that for sufficient numbers of people is a maternal brand, should be a licence to print money.

But these brands are under a new threat beyond the traditional own label foe.

They are under threat because they don’t believe in the stuff we believe in, indeed they often don’t believe in anything.

My 39 year relationship with Andrex must have been worth an astronomical amount to Kimberly Clark. I have been using Andrex to wipe my bottom and blow my nose since I came out of nappies.

But it is a relationship that I have recently finished. Finito. No farewell, no tears, no regrets. Presumably Kimberly Clark don’t even know what happened and care even less, because this little parting doesn’t show up on their metrics, at least not yet.

It is just that I felt that I can no longer buy loo roll made from virgin paper and so Andrex has become totally incompatible with the way that we chose to lead our lives as a family.

Brilliant loo roll it may be – soft, strong and very long as its advertising tells us – but it doesn’t care about the things I care about, it doesn’t believe in the stuff I believe in.

My children will not grow up with Andrex as a maternal brand. And all that revenue will slip away from the Kimberly Clark empire.

And I can see the same thing a happening with Anchor butter. I have eaten Anchor since I was weaned sometimes in the late ’60s, never once perturbed by the idea that shipping yellow fats 11,000 miles to the UK might not be a brilliant idea.

But Anchor stands for nothing, believes in nothing, has no point of view about my life or my family’s life. Lurpack does. Thanks to Wiedens Lurpack believes in food – good, honest, natural, tasty food. And it stands against ready meals, lazy food, fast food and junk. That sounds like my brand to be honest because it believes in the something I strongly believe in. Now of course this is a very recent conversion, but I am willing to believe even at this early stage – lets see if their belief is only ‘ad deep’.

Now these may be an utterly isolated examples from a wanker that works in adland and has more money than sense. Perhaps.

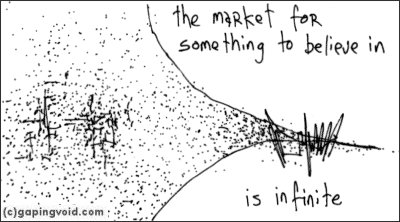

But as Hugh at Gaping Void says “the market for something to believe in is infinite” and the brands that are capturing our imagination and our money at the moment from Innocent to Dove now stand for something you can either actively reject or get fully behind.

I call this this the brand’s ‘position’ after one of the theses in the Cluetrain Manifesto: “Companies attempting to position themselves need to take a position. Optimally it should be relate to something their market actually cares about”.

It would be of little concern to anyone if also ran brands were to fall by the wayside in the face of consumer affection for brands that are aligned to their values, but whatever we think of these maternal brands intellectually, emotionally they matter to us. And their current fragility must be of concern to all of us interested in the brandscape.

I guess by and large maternal brands are the success story of the era of mass marketing. We have very emotional relationships with them because we were brought up on them but perhaps for our parents and grandparents these were simply the brands that were in full distribution, of reasonable quality and marketed strongly, particularly through TV. It’s something Seth Godin calls the TV-Industrial complex – ads buy distribution, buys share, buys profit, buys ads.

And it was watertight for so long because the barriers to entry were so high, because size bred power and because lets face it by the standards of the times the products worked brilliantly.

But I’m afraid that these days I want my brands to be on my side – not just providing a service to me at a reasonable price and with guaranteed results.

I want my brands to care about my life, not just their job.

And if my maternal brands don’t shape up, they will inevitably be shipped out.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Cool.

Brilliant. Now if we could just work out the ROI!

Nice post. One point – I prefer human beings to care about me, brands on the other hand – I can take or leave. But then that’s just me I guess :-)

Do I detect from your 3rd paragraph that the Labour Party was once a maternal brand for you? Is it still? Or does it no longer stand for anything?

On another note, I am not sure that Andrex or Anchor necessarily lack potential for adopting a position on things that would go down well chez Huntingdon. “We are happy cows, we chew the cud and browse” could easily extend to a belief in animal welfare, and Andrex’s softness could extend far beyond the rectum to the world in general.

This does raise two questions. 1) Should all brands be politicised to this extent and 2) will the brandscape become a bit tedious if all brands unfurl the banner of fashionable left-liberal environmentalism?

Noone is saying that the left-liberal cause is the only position a brand can hold: Dove is politically neutral, The Economist, Johnny Walker, etc are highly individualistic. But there is a danger in certain sectors that everything becomes a bit treehugging.

On another note, I assume that butter is transported by ship not by aircraft, and hence you can relax a little about the environmental impact. I am a little nervous about the food-miles movement as in many of its effects it would be indistinguishable from food racism – for many poorer countries agriculture is the only export industry they have.

The Labour party was certainly not a maternal brand for me Mr Sutherland. To stand against the scorched earth policy the Tories exacted upon this country over 18 long ghastly years is not to suggest any affection for their political rivals. Indeed, there are very few parties that can accommodate my federalist, republican, atheist world view full stop.

It doesn’t matter what point of view a brand holds as long as it has one and it chimes with sufficient people to work. There is no ‘left-liberal’ monopoly over opinion – you are the living proof of this. And it is not about politicising brands either. In the good old days before it tottered of to Mother for some half hearted mining japes, Pot Noodle was a strongly opinionated brand.

I totally agree with you on support for the agriculture of poorer countries (New Zealand is not one of them) and given half a chance I think there is a brand opinion that embraces globalisation – HSBC perhaps?

Perhaps you’ve out grown these maternal brands – it’s just taken longer than it has to loosen all those other apron strings?

Then again, we live in a different world to the one we lived in when your brands first cradled the bosom. For example, in buying Persil and Andrex your parents may have been wanting to say something about how they brought up their family. In many areas those lines are now less clear. People will happily spend £2 on an organic loaf of bread and then rave about the flight they booked for a quid.

I can see our children growing up with innocent and anything with ‘organic’ printed on it as a strong maternal brand.

But I fear that when our kids are teenagers they’ll say things like, “Father, would you please refrain from using obscenities when my friends are visiting. And if you must insist on using that scarce fossil fuel please park the polluting vehicle well away from my bedroom window.”

Now, this federalist, republican, atheist thing you speak of. Where do I sign?

Techically you should avoid butter, not specifically NZ butter, if you wish to benefit the environment. Vegetarianism and the boycott of anything bovine being a good first step to saving the planet.

http://www.virtualcentre.org/en/library/key_pub/longshad/A0701E00.htm

The Slag of All Snacks was perhaps the greatest endline of al time, by the way. At least for the all too short period before it was banned: and banned for what, exactly? Is there a lobby group for slags?

Federalist? Atheistic? Republican? The Scottish Nationalists would seem to satisfy all three.

Knew there would be a catch.

Absolutely.

I worked out the other day (and was going to post on)that my longest unbroken brand relationship is with Colgate Total. I’ve used it pretty much since launch (early 90s?) without ever being tempted to change.

That maternal thing can be a hazard though. Look at Marmite, they were struggling in the 80s because people only ate it as kids, then fed it to their kids. No one bought it when they got older. They brought in the “Love / Hate” campaign and sales went up again.

The Slag of all snacks was pure genius, and for one key reason; it was absolutely the truth about the brand. People understood that, expect for the Neo Whitehouse brigade.

The Organic movement is one of the most extraordinary marketing successes of the age – how to sell filthy, misshapen vegetables to your most credulous middle class customers at a massive premium.

What is so interesting is that, like all marketing successes, it is based on a slim product truth. There are categories (meat, in particular) where organic produce tastes noticeably better. There are a few other areas – organic milk for kids perhaps – where there may be some scientific basis for the premium.

Yet in 90% of categories it is more or less plain snobbery and not much else.

And noone seems to notice that the Organic Movement is in direct conflict with the climate change movement. Surely it would be a good idea to, er, reduce the area of land under cultivation rather than increasing it?

The organic movement is a testament to the power of brands, and just how they are able to produce confusion in the mind of the consumer – by being snobbish, as you say Rory, people contradict certain principles they claim they are committed to.

And as for HSBC supporting globalisation; I’m not convinced they support anything – precisely the reason I detest the campaign is because it doesn’t assert anything (barring ‘having a point of view’).

Might as well have said ‘think’, and be done.

As for maternal brands – I definitely think there is something to be said for outgrowing brands as you get older/your priorities change.

As a 22 year old, I like designer labels. Did from when I was probably 5 years old. But when I become a father of two.. I think it’ll change.

I wouldnt say HSBC is supporting globalisation per se. Their ads and brand ideas seem to be much more about celebrating and understanding the differences in culture.

I always think the ultimate in brand loyalty is parents who buy expensive branded clothing for their newborn babies, each will last them probably a matter of months; yet they are happy to shell out again and again.

But aren’t parents just ‘using’ designerwear baby brands for their identity value?

I suspect any prospect of a Burberry buggy went straight out of the window once its Chav associations reached critical mass!

More generally, agree that maternal brands are losing their way; that nostalgic appeal alone may wear thin as generations tick over.

But equally not altogether sure that the Doves of this world are the next bloodline of nostalgic brands either. As indirectly contemplated here

http://culturemaking.typepad.com/main/2007/03/the_cultural_re.html

Sooner or later, perhaps ‘real beauty’ might not seem quite so ‘real’ anymore?

Anyway, great post all the same.

Seems like you’re suggesting we’re living in a world where Tradition exerts a considerably weaker influence than it used to… a world in which traditional institutions (be they social groups, centres of cultural meaning, etc.) are much less able to replicate their values, POVs, and behaviours.

Are brands much less able to pass on their genetic material these days? Tradition certainly isn’t what it used to be. And the plethora of other options is too vast to be unimaginative in one’s choices.

Are we less likely these to (re)adopt the brands our parents bought for us/gave us?

I’d be fascinated to see any data that would support this. I’m sure one could begin to construct a story with a few decades’ worth of TGI, for example.

Brand choice – product of nature or nuture these days? Discuss!

Mr Huntington no longer with the AA is a real shock – the new car was a real shock too.

Now I know this website is not for the Huntington family to swap family news, but we are a bit dispersed these days.

Moving to America has forced me to be seperated from most of my material brands, but on leaving home I too took all my childhood brands with me for many years.

I think I dropped most of the ones Richard mentioned a little sooner though. Andrex went out the window 18 years ago when I switched to recycled sandpaper while at University. Persil lasted a bit longer being replaced by an eco friendly brand maybe 5 years ago (which is available in the US). Anchor butter went at a similar time (marriage brings material brand conflicts) resolved by buying organic and local.

All of these brands could have survived in my household if they had moved with my values.

Perhaps there’s a natural cycle to these allegiances: we adopt, then adapt, then pass on?

I look at my grandparents, parents and myself and can see consistent brand seams (Colgate, Barclays) and others which, while they survived the leap to one generation, didn’t make it a second time.

I’ve ditched “maternal” brands for all manner of reasons–washing powder because I really don’t care what brand I use; The AA because I was offered a cheaper alternative. Yet others have already rooted with me.

I suspect that’s a process which will continue and accelerate. And as our society ages, ownership of that calcified brand landscape will be all the more important.

I think Richard is actually making two points worth exploring. One about how brand relationships can be lost by not keeping up with people’s values (fairy liquid is another casualty). It would be interesting to do a brand audit of the Huntington parents to see if they have kept many of our childhood brands.

I assume brand managers have a conflict to deal with between keeping up with changing values vs. maintain the brands own values. I assume Lever Bros and P&G have brought out new brands to try and match our changing values but have not capitalized on the existing brand relationships.

The other point is about children’s adoption of brands. Children believe their world is the only world, so if a family only uses Andrex then Andrex is the only loo roll in the world – or the only right loo roll. Our parent may have used a brand not out of brand loyalty but just out of pure price/convience/quality reasons, but if there was consistency then for a child a very different relationship is created. That relationship is broken when a person develops their own personal values and realizes that they don’t match that of the brands they are using, but this may take many years as Richard has illustrated.

Other interesting Huntington examples: I once had a brand loyalty to Esso petrol, one I got from childhood but not a brand loyalty I think my parents had. I stopped using Lilly (?) pasta when I discovered it was lower quality than Sainsbury’s own brand pasta from a buyer at Sainsbury, until then I had never questioned the pasta’s quality.

Anchor does believe in something, feeding cows fresh green grass all year round, something your parents may have bought into which at some point persuaded them to buy it, a behaviour you’ve followed ever since. It’s not based out of belief or maternal affection, but because we avoid making decisions where possible, simply because there are too many in life today, so it’s easy to avoid them and buy what we did last time. The maternal connection happened once, when you left home and bought the same, since then you’ve been buying what you normally do. Ehrenburg’s static market hold’s true.

And since you believe in not shipping yellow fat long distances, why not buy Country Life? It’s from England, launched because our 2 leading brands were imported, something they’ve made a West Country song and dance about since launch. Besides, 3 English dairy farmers leave the industry every single day due to lack of support, so I would urge you not to import Lurpack from Denmark when we make perfectly good, and cheaper, butter here.

One interesting possibility is that maternal brands and their hereditary relationships are being destroyed by the massive expansion in further education in the UK and elsewhere. Especially among women.

Quite a few people from the “I’ve moved away from home and am massively more enlightened than my blinkered and provincial parents” crowd – e.g. half the population of London or New York City – seem to reject everything about their parents, brand selection being a small but significant part of this. Politics being another.