12. Performance

Performance is perhaps an odd topic when talking about brand strategy.

In fairness I could have called this conversation – presentation. The way that you communicate your strategy to those around you, your stakeholders or in the case of agency people, your clients.

But I’ve used the word performance because it suggests a level of engagement above simply presenting. For me, a presentation is when you literally present something to people. In other words there is an object or subject and you want to show it to them. That object is the interesting thing not you, so you present it – in our world often using charts, certainly with some form of document.

Perfomance is altogether different, it’s when the interesting thing is you and what you are saying. And if you use charts it’s to illustrate or support your performance. And often when we talk about presentation skills what we re really talking about is the skills of performance.

And performance is important in brand strategy, or indeed the communication of any important ideas because its the means by which you get other people interested in your thinking, from colleagues to clients to client stakeholders and so on.

For all our conversation about the commercial value of brands you are going to have a tough time convincing people of the precise return that a stronger and healthier brand is going to deliver for you. The sheer intangibility of this value, sitting as it will inside the minds of thousands, maybe millions of people’s minds would make this endeavour fanciful. You can offer examples of the transformative power and commercial punch of other brands, though they will never be your own. You can suggest the impact of a certain number of customers buying or buying a little more because of the strength of your brand, though the number of assumptions baked into this may make it a slightly arbitrary exercise. You may do some research with customers on some of the outputs of your work but it will be hard to replicate the way people will feel when the work you have done is actually out in the world.

Put bluntly, you are not going to be able to conclude your conversation with a dollar value, except to suggest what implementing your plan is going to cost. So you are going to need to be convincing. And that’s where the power of performance lies. You are going to use your performance to win people over – colleagues, investors, your board and clients, basically whoever you need to support you to deliver your brand strategy. Basically you are going to need to get good at performing.

Indeed I now believe that Strategy is at heart a performance art.

I have made a point of turning performing into an ace. There are many things in the world that you may be good at, really good at but aces are the things at which you are world class. There will only be a handful of activities or skills that you possess to this level but you will be Jedi level good at them. Performance is one of my aces.

To be clear, this type of performing has nothing really to do with acting or elocution or stage craft of any sort. It’s about how you engage people with you personally and therefore the story you are telling. If strategy should have heart and passion baked into it then this is when you convey that emotional to others.

While its phenomenally difficult to demonstrate the idea of performance in through the written word I am going to do my best to illustrate the basics of a great performance.

Opening

My advice is to start hard and fast. No messing about with introductions and preambles. Walk straight in and start with passion and energy. Captivate people from the very beginning and get them in the state that you want them.

The subject you are going to talk about may not be a question of life and death but there is often a jeopardy behind the conversation you are having – a brand or business that is not in great shape and requires an intervention. And the work that you have done and are delivering is about to change all that. Or at the very least is going to offer a ray of hope and optimism.

So, bring the energy even if the room seems bereft of it. Jump start the audience into engaging with you and the story you are about to tell.

And make it clear from the start that this performance is not going to feel like double maths. Double maths was what happened on a Monday morning at school when in a timetabling disaster two maths lessons were scheduled back to back. Unless you are Stephen Hawking that’s a pretty horrific start to the week. And how many presentations and performances have you sat through that are so dull, turgid and boring that they might as well have been a double serving of your least favourite subject?

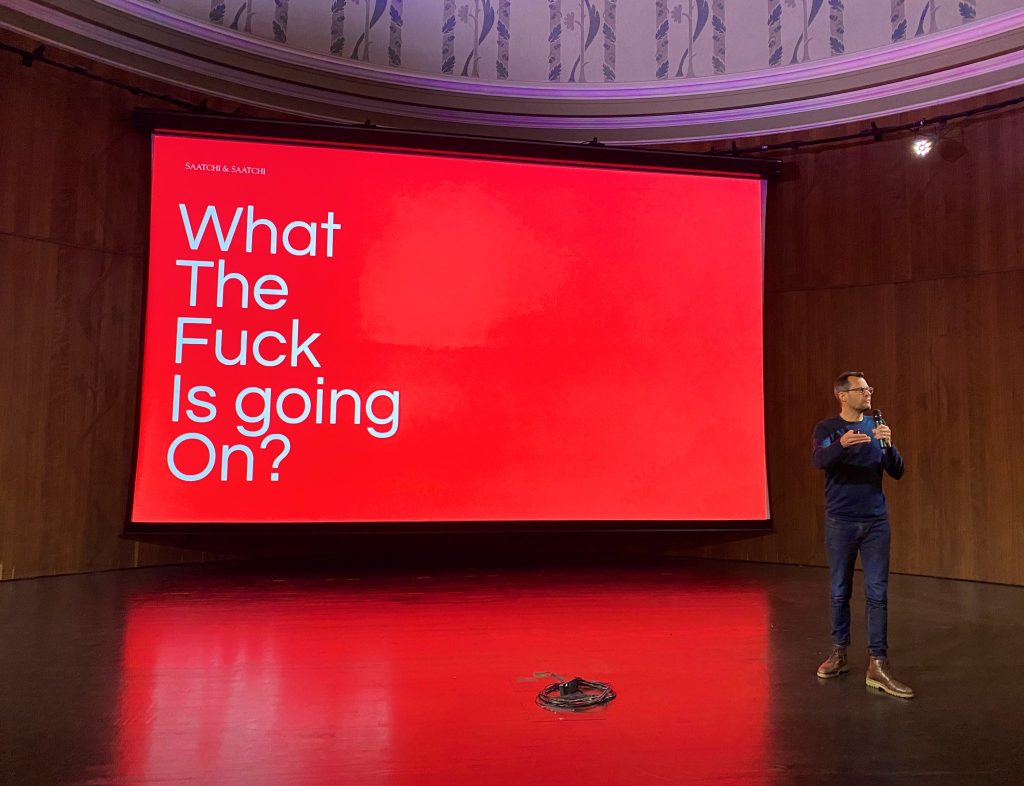

So I always try and do something very early on that makes it super clear that the time that you spend with this group of people is going to be fun for everyone concerned. It’s usually a story that serves no other purpose than to put people in the right frame of mind to enjoy where I am about to take them. Be brave with how you do this – a striking image, a piece of music, a video clip. I recently did a talk in which the third slide simply said ‘What the fuck is going on?’ in letters that took up the whole of the screen, from that moment the audience knew that there was to be no double maths.

The short hand for all this is what I call a hard start.

Narrative

I am fanatical about narrative.

Narrative is the journey that you take people on. It can have detours and diversions but at its heart is a very clear story that takes you from start to finish. It needs to be crisp and simple so that no one is lost along the way and it will probably have three or four moments that you really want to land and have the audience remember.

These days people write decks all the time. As if that’s the only way in which humans have been able to communicate. Decks are fine, I sometimes start a presentation by building a deck and seeing where it takes me. But they must never stand in for narrative. Just because deck software of any stripe is linear that doesn’t mean that it will magically create a narrative for you. You are far better off building the basic structure of your narrative in your notebook to the point where you are able to tell anyone the essential arc of your argument with no notes and certainly no deck.

It’s not that you will be asked to deliver an elevator pitch but the point is that you could. At this stage you will have a lovely clear narrative thrust and everything else you do or say will add colour, drama and proof to that narrative. That’s why, even when I move to the deck, I start merely with a skeleton that walks through the argument. I do this in black and white in a default typeface so that there is no window dressing, the narrative is either clear or it isn’t and no one is distracted by the quality of the design or the data that supports the conversation. If people in my team buy the argument I can go and sandbag it with proof, stories, and beautiful design.

And if the narrative ever gets messy or meandering the best thing to do is get back your skeleton narrative. Write it out again in long hand. Ask yourself what the seven to ten key moments are in the story upon which everything hangs. Once you can see the narrative clearly again, you can go back to your deck.

Because we are talking about brand strategy the narrative will start with your strategic spine. Beginning with the first principles you have anchored your entire strategy in, you can then lay out the decisions that you have made in building your strategic spine. Then, you will be in a position to reveal your brand idea and unpack how powerful it is, both in terms of the territory it allows your brand to occupy and in its expression and implications. Perhaps showing how the activities and behaviours of the business would be changed by this idea across the spectrum of experiences people will have of it.

It’s rather wasteful I know but there are few better ways to understand your narrative at this point than to print it off and stick it on a wall. This allows you to see where the logic gaps are and to easily change the order of your argument.

Proof

Precisely because your recommendation is going to be short on the return that your thinking and activity will have on the business in terms of precise revenue or profit, you are going to need to prove your case. Not prove it beyond doubt for your accountant but prove to the audience and your stakeholders that there is method in your madness, that this approach you have is likely to solve the problem at hand.

There are three moments for proof.

In justifying the decisions you have made to build the strategic spine. Proving your spine should be methodical, blending the data and qualitative evidence you have to support the decision making in this section of your performance. Here the proof you use will offer the option between two or more gates and point to the right decision. It should feel very logical.

But when you are unpacking and expanding on your brand idea your proof can be more expansive and eclectic.

There will be proof that represents the clues that you have unearthed about the direction you want your brand to go in. This will be used in the build up to delivering the idea. A piece of data that opened up the territory you are interested in. A famous quote that came to mind. A conversation you overheard or listened to in qualitative research. You will want to gather these clues and scatter them like breadcrumbs in the build up to your idea.

Then there will be the proof that tells people that you are right. You will use this after you have revealed the thinking in order to sandbag the answer. I like the image of sandbags because it feels like you are building up a mountain of evidence so that the answer is supported and solid. If the first stage of your performance used proof sequentially, the second uses it concurrently. By which I mean it feels like you surround an idea with evidence from lots of different places and angles so the idea is fully protected. Its the strategic equivalent of saying ‘that’s not all, here is another thing’. The weight of evidence seems to come from so many different places and sources that there is no room to escape.

Your job is to overwhelm the audience so that they are bought in to your approach and also incredibly excited by the answer. My action standard is whether people believe by the end that everyday that goes by without this brand strategy in place is damaging for our future and risks someone else coming along and doing it.

Romance

Romancing an answer is about coaxing it and nurturing it. Making it feel welcome in the world and critically making the audience feel ready to buy your idea. I talked about the breadcrumb like clues that will lead you from your strategic spine to the reveal of your brand idea. This is where the romance happens. You don’t go straight to the reveal but warm people up, get them in the mood.

When I was selling in the ‘promise’ strategy for HSBC Life I had already pointed out that the rest of the bank dealt in plans but the Life business dealt in promises. In fact, it was the only part of the bank that promised people anything. That section was about giving those clients a sense of mission and identity. The romance came from appealing to the parents in the room.

Anyone who is a parent and perhaps anyone who has been a child, knows that a promise is a promise. As a parent I learned that you never promise your children anything that you don’t categorically know you can deliver on. And they are important because children don’t understand yet that people break promises all the time. At that moment I was romancing the promises idea by grounding it in the hearts of the audience with a personal story that I knew that virtually everyone in that audience would understand and embrace.

It need not be a personal story but you do need to find a soft landing for the idea you are about to deliver, one that builds up to it gently so that when you deliver that idea it seems to be the most natural conclusion in the world no matter how radical it is.

Bringing the romance creates the perfect conditions for you to win people over to your brand idea itself.

Drama

All performance should have drama. The role of this is to create emotional peaks and troughs that carry people with you but also set up the high of the answer in comparison to, say the low of the problem. This is not usually a straight progression, in fact what you really want to create is a couple of inflection points where you catch people out by guiding them somewhere and then suggesting that this is a dead end or would be the wrong answer if pursued further.

A good infection point for instance would be to set out the problem clearly and precisely, making it look simple and straightforward and then say ‘if only it was that easy’. This is the point at which you then reveal the real more fundamental problem at hand. The one that others are overlooking. This is a classic use of drama that helps focus attention because it suggests the issue is rather more complicated than the audience thought.

You can do the same thing when you are building towards an answer. Take the audience down a line of thinking or approach and then ‘pull the rug’ from under it by arguing that this approach would be a mistake or miss the real prize.

When you have your narrative set out you can start to think about the moments where you want to bring a little drama to the proceedings. Creating inflection points or ‘turns’ in the narrative structure.

Drama can also be created in the cadence of your delivery. By altering your intensity or energy you can draw people closer into your thinking so that they are almost up against a pain of glass peering inside. Or you can have them swept along on a tide of energy and rhythm that has then arrive at a conclusion which barely knowing what has happened along the way.

Perhaps you slow everything down with some data you want to investigate in detail that requires everyone to get really close and find their way around that detail guided by your calm, measured voice. Or it could be a story from research or your personal life, one where you bring people inside the detail.

And then pull back out again, delivering a rapid succession of facts or conclusions that you must infer from those facts that carries people along. One of my favourite approaches is to expand or contract. So you might observe something about people’s lives, their relationship with your category or the wider world from your data, research or story. And then start expanding out, suggesting that its not only true of that particular circumstance, its also true of the whole category, and its true of wider culture or society. And as a coup de grace, that its never been more true than today.

Contracting is simply the reverse journey, starting broad and then zooming into your category or customer. Which ever approach you use, always finish on the sense that this has never been more true. So when I was a talking about promises for HSBC Life I started in an expansive sense talking about the power of promises in every part of our lives, then go super specific using the fact that the word ‘promise’ is printed on every bank notes that HSBC issues in Hong Kong. Then I pivoted to a conversation about fake news and broken promises to deliver the sense that the idea was never more powerful than it was right now’.

Finally, or at least finally from me as I suspect you will find your own ways to bring drama into your storytelling, are jeopardy and risk. This is when you suggest the problem in not taking the path that you are advocating. This is important precisely because it is difficult to prove a dollar value from adopting one brand strategy over another. So you want to point a picture of what happens if you ignore or reject this approach. The simplest way to do this is to invoke the spectre of a competitor getting there and how problematic this would be. But the thing I really like doing is to suggest that everyday that goes by without this approach in place, that you are doing the business or organisation harm.

This is exactly how I ended the original Direct Line brand strategy. I had taken the expression of the strategy in the form of the fixer ‘Winston Wolfe’ out to customers in qualitative research and I had seen the response people had to it and how people latched onto the idea of an insurance company that wanted to take their problems away rather than give them a big hug. It created real drama in the conversation with Direct Line because it allowed the strategy to end on a moment of absolute conviction. That there was a real and very expensive opportunity cost of not adopting our approach.

Drama is not theatre. Theatre is show, drama is showmanship, the way that you move people to conclusion by moving them emotionally. Drawing them in and pushing them out, taking them down dead ends only to dismiss that approach or building them up on a tide of energy to the place you want them to be.

This is why strategy needs performance not just presentation. Because while it has logic hardwired into it from the start and particularly throughout the strategic spine, it needs to be bought and bought into emotionally as well as rationally.

Use the full force of powerful openings, blistering narrative, un arguable proof, unmissable romance and drama to land your brand strategy in people’s hearts as well as minds.

And you will see why you need to be a great performer and not a great presenter.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.