Do I not like crowd sourcing

Talk about jumping on the band wagon some considerable time after it has packed up and left town, Peperami is the latest brand to indulge itself in a little spot of crowd sourcing to support their nibblers sub-brand under the thought that they are 'a little bit of an animal'. And harmless fun this work is too. Devised by err, two advertising creatives through the Ideas Bounty website it is a mildy humourous retread of the classic Lintas work of the ‘90s.

But why, what on earth is the point of crowd sourcing? I just don’t fucking get it.

Firstly while I’m all for finding new and more fundamental ways for people to engage with brands, I’m not sure getting them to make ads is really what we all mean by engagement. While it offers deep engagement for those that can be arsed to do your job for you this approach requires so much effort it only ever touches a phenomenally small bunch of people (1,185 people submitted ideas in this case) and this type of engagement is restricted to the communications the brands makes and nothing more substantial.

Secondly this approach is surely best done with the fans and advocates of the brand and not through websites like ideas bounty which is simply a marriage broker for creatives and clients and not really about crowd sourcing at all.

Thirdly, what’s so cool about crowd sourcing anyway? It strikes me that clients that have no real strategy are being sold it as a 'brave new idea' in communications when its just a bit of PR puffery to mask the fact that no one has any genuinely new ideas about the brand themselves. Does anyone give a shit who writes an ad whether full service agency, creative independent or consumer as long as its brilliant and it works?

Fourthly, surely crowd sourcing should be about engaging the wisdom of the crowd to create something new and interesting but what we get here is a ‘90s Lintas ad that's not quite as funny or interesting precisely because it’s a retread of old work and an old idea. ‘A bit of an animal’ was powerful for the brand when it was conceived because it broke the conventions of the category’s advertising and, along with Tango and Pot Noodle (both from my alma mater HHCL), rewrote the rules of advertising for a generation.

And that’s one of the frustrations at the heart of crowd sourced ideas of this nature, they can’t move the brand on because the crowd can’t see beyond the advertising vehicle for which famous brands are famous for.

You can see what I mean for yourself if you haven't already seen the ad.

I don’t know about you but for my money crowd sourcing needs to be filed next to opening shops in second life as silly nonsense the industry momentarily got excite about but serves no real purpose. But then I would say that wouldn’t working for a dirty great full service agency as I do.

By the way if you are remotely interested the ad goes on air on Monday 23rd August. And if you aren’t here is a taste of genuinely innovative work from the brand in its hey day.

And yes I think that is the late and much missed John Peel.

More sex please, were British

.jpg)

Image courtesy of Dave Gorman

I have long believed that advertising is not a profession. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not embarrassed about what we do and I certainly have little sympathy with the sentiment of that terrible old joke. You know the in which someone asks that his mother is not told that he works in advertising since she thinks that he is the piano player in a brothel. However, there are a number of reasons why the idea that what we do resembles a profession rings a little hollow.

Firstly you need no specific qualifications to practice advertising, one of the primary criteria for any occupation being seen as a profession. In fact you need no qualifications whatsoever to do what we do and be very good at it. Secondly there are no professional bodies to which you have to belong, that police the profession and from which you can be expelled for malpractice. Sure there are industry associations that agencies and clients are encouraged to join but membership is not compulsory. Thirdly is the small matter of what we get paid for. Where other professional service firms sell certainty we sell only possibility.

Real professions offer certainty because their expertise in a particular area allows them to predict the outcome of their recommendations accurately. That’s true of lawyers, accountants and even management consultants when they stick to the supply side of the value equation.

That simply doesn’t happen in advertising. Expertise and knowledge are valuable but they aren’t really the reason that people use our services or the services of one agency over another. Because that expertise can’t in itself guarantee the effect that creativity will have on customers and the outcome this in turn will have on their business. You can have a feeling for the work and you can research that work but you never really know what is going to happen in the real world. This has never been more true than now because the real media with we work with is no longer television, print, outdoor or even online or search. The real medium we work with is the degree to which people are interested in what our brands are doing and want to engage with it. Try predicting that!

The traditional response to this has been one of denial. To ape the professions in order to add a veneer of certainty and responsibility to what we do. To bang on about accountability, return on investment and wear a lot of very dull grey suits to prove that we are serious.

I want to advocate a return to an industry that believes in sex. Not in our work but in the way that we behave. What advertising people used to understand is that to sell ideas that engage the right hand side of our brains and those of our customers we need to create an atmosphere that is conducive to this – sexy agencies. And in order to land recommendations based on conviction and not certainty we need to build personal relationships with clients based on mutual liking - sexy people. This is the reason that an agency of any discipline gives up its sexy location for somewhere cheaper, stints on the front of house service, or employs talented but dreary people at its peril.

In advertising our recommendations rarely sell themselves, they need help. That is why it is time to dump our pretence at being a profession and recognise that for us all, sex sells. Maybe the idea that we play the piano in a brothel is actually a rather good metaphor after all.

This post appeared originally as a column in New Media Age

Who is to blame?

Image courtesy of Planoscorpio

Say what you like about Cannes but at its best it still serves as a barometer for where our industry and our product is heading. Most notably the Titanium shortlist, packed as it is with the coolest work from the coolest agencies and representing the new creative dividend that is on offer to brands that put participation at the heart of their work.

But the obvious question is that if this is the sort of work we all admire from the sort of agencies we all admire how come the UK is so poorly represented? Having offered the industry creative leadership for so many years is our inability to compete with the Droga 5s, Crispins, Goodbys and Nitros of this world proof that the UK is to be a foot note in the future of creative communications?

Ok so the Great Schlep emerged from a unique set of historical circumstances and perhaps its unfair to flagellate ourselves over much for failing to deliver campaigns of this nature day in day out. However, work like Queensland’s ‘Greatest Job on Earth’ and the Whopper ‘Facebook Friend Sacrifice’ came from the kind of briefs that grace our desks on a weekly basis.

So where should we lay the blame for our inability to capitalise on the new creative dividend? Who exactly, in the parlance of our times, doesn’t get it?

Well it sure ain’t the great British consumer that is getting in the way. Educated by Google, trained by Ebay and connected by Facebook our consumers are quite clearly ready to play and in substantial numbers.

And it is genuinely no longer the agency world that is dragging its collective feet. Sure the orthodox advertising agencies may have been a little slow on the uptake but once we got with the programme ur ambitions, attitudes and capability to deliver the campaigns of the future changed radically.

No, without a doubt the people struggling hardest to ‘get it’ are within the client community. It is their silo’s, their pre-testing regimes, their moribund metrics, their accepted wisdoms, their fear of risk, their politics and their obsession with short-form TV advertising that is the most significant break on the greatest future facing work coming out of the UK. Sure there are some inspirational marketers inside our greatest brand owners but invariably they sit at the helm of organisations that struggle desperately to brief and buy campaigns that have even one foot in the twenty first century.

For UK advertising to lead the world again we must now ask our client community whether it is prepared to step out of its collective comfort zone and become once again the patrons of revolutionary marketing.

This post originally appeared in a column in Campaign

Is it the end of the line for the digital agency?

Image courtesy of Ackers-Schoolboy Hero!!!!

Some time in the early summer the Met Office rather confidently predicted that this would be the summer of the BBQ, so hot, dry and altogether splendid was our weather going to be. Alas it turned out to be a rather different meteorological kettle of fish and once again this summer has been unremittingly dreary, anything but the summer of the BBQ. Similarly at the beginning of this recession the soothsayers of the digital community rather confidently predicted that this would be the recession of the digital agency, basking as they would be in the sunny glory of a much-trumpeted culture of accountability. More than that, it would be the death of those sad old orthodox ad agencies that in the parlance of our time simply ‘don’t get it’. Alas, if you are a digital shop it is turning out to be anything but your recession. Good news for digital, bad news for the rather quaint idea of the standalone digital agency.

Indeed the orthodox agencies will emerge form this recession stronger, better, leaner and with the lion’s share of the business that used to be the preserve of pure play agencies as the latter struggle to play in the big league or face annihilation.

In many ways this is simply because at long last client organisations are taking digital seriously and Marketing Directors in particular now see it as part of their core responsibility rather than something rather marginal that can be delegated to someone keen and junior to look after. And with contemporary marketing involving so many disciplines demanding the attention of your average marketing chief, there are real advantages in integrating as many of these into as few agencies as possible. Preferably the agencies they work closely with and trust most. In some cases theses are digital agencies by birth, in many cases they are not.

Of course we have long acknowledged the inevitable convergence of the two agency worlds since the division of labour that we currently tolerate is utterly ludicrous, not least because it sustains at least two sets of pointless overheads that clients are inevitably paying for. However, recessions cause more dramatic adjustments in the market and there is a very specific and powerful new factor at work that will significantly accelerate this process. The fee negotiations that orthodox agencies are involved in to secure their retainers for 2010.

Orthodox agencies may have been the brunt of digital jokes about pathological slowness, limited creative ambition and a culture that doesn’t get interactivity and participation but that has long ceased to be true. They have got with the programme and if not hired the programmers certainly hired any one else a bit tasty in the digital world. And armed with this capability and ambition CFOs are marching into fee negotiations poised to take out the standalone digital agency with a finely crafted remuneration proposal. A document that promises significant cost savings for the Client’s budget and moderate increases in revenue for the agency by rolling the brand’s digital scope into the responsibilities of the lead advertising agency.

The only solution for stand alone digital agencies in the face of this tsunami of excited finance directors is either to follow the lead of the media agencies and create vast buying points for commoditised production capability or to develop such strong creative or technological specialisms that they remain of greater value to their clients than the bigger scope deals that are on offer from the orthodox agencies. Otherwise it is not just the BBQs digital agencies should be worried about but their lunch too.

This post originally appeared as a column in New Media Age

Brand respsonse - a case of having your cake and eating it

Image courtesy of Blake E. Marquis.

Eddie Izzard has a standup routine about how useless the Church of England would have been at the Spanish Inquisition, because everyone appearing before it would have been given the option of cake or death. Naturally most people end up choosing the cake option.

The choice is somewhat less clear in the world of marketing. With marketing budgets that used to dwarf our national debt now stripped to the bone by voracious bean counters, marketers face a choice of whether to spend their slim and hard won resources on brand or response.

Every fibre of their being knows that to mortgage people’s long term relationship with the brand on tactical and temporary sales driving activity alone is an act of pure folly. That’s what their training has taught them, that’s what the marketing text books tell them and that’s what their advertising agency takes every opportunity to remind them of.

And yet with real pressure on the business the imperative will naturally be to divert all their funds into lead generating activity both off and online. And with their direct and digital agencies dangling the carrot of bargain basement cost per response online no one is going to be fired for making that decision. This dilemna between response and brand is what in a less elegant past we called jam today or jam tomorrow.

Well it may well be possible to have your cake and eat it complete with lots of jam. Help is at hand in the form of an approach that goes by the imaginatively named title of brand response. Can you see what they did there? Now admittedly at first sight this idea appears to be a monumental fudge that’s almost certain to satisfy neither the objective of building an enduring relationship with consumers nor building immediate sales. And it probably is if you simply take your brand work and slap a harder sales message and call to action onto it and hope for a decent response.

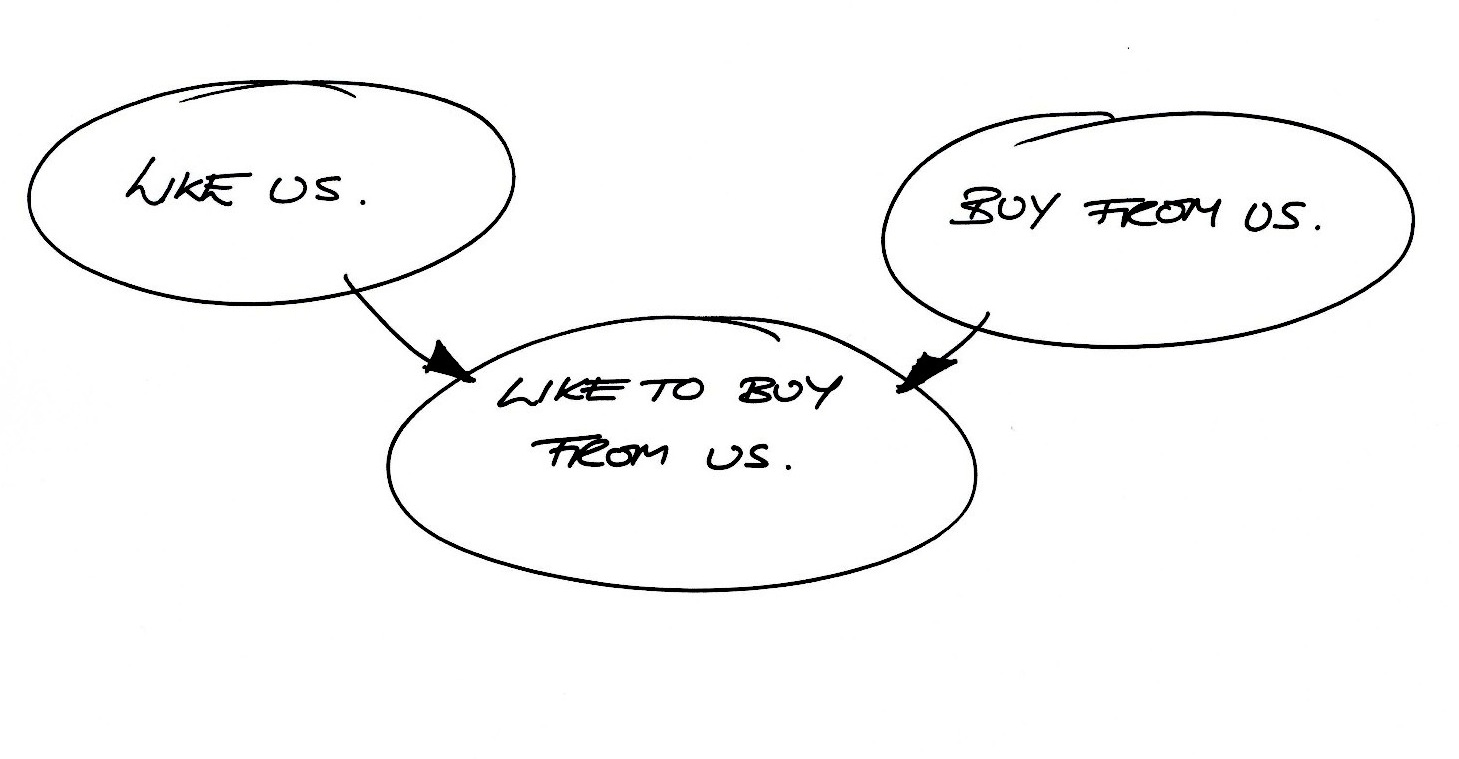

However, real brand response activity approaches the problem strategically not just executionally. If the primary objective of brand advertising is to get people to ‘like the brand’ and the primary objective of direct response advertising is to get people to ‘buy from the brand’ then the objective of brand response advertising should be to get people to ‘like to buy from the brand’. And that means not just dumping value claims and offers into the market in the way direct response does but also delivering a compelling context for that claim. The context that ensures consumers understand the reason the brand is offering that deal. And right now that’s a fundamental reconfiguring of value in the lives of consumers, what we might call a new-value mindset.

Sainsbury’s gets this and right now excels at imaginative brand response marketing. Under the ‘like me’ brand idea of try something new today, initiatives like ‘love your leftovers’ and ‘feed your family for a fiver’ have people queuing up to buy from the brand and loving every moment. Small wonder that Sainsbury’s are taking the predominantly response driven Tesco to the cleaners.

Which leaves us wondering what a new world pf brand response means for digital. Online brand activity seems far more segregated into ‘like the brand’ and ‘buy from the brand’ than offline, into apps and experiences on the one hand and cheap and cheerful direct response advertising on the other. Fine if these are just tools to compliment other marketing activity, but not much of a future as a stand-alone industry. Perhaps its time for the digital marketing community itself to make a choice between cake and death.

This post appeared originally as a column in New Media Age

How come Sainsbury's is doing so well and Tesco isn't?

Image courtesy of avlxyz.

I love Facebook. But its not often I stumble across a real revelation there. Not so a couple of weeks ago when a feed from Paul Mcenany's excellent blog heehawmarketing popped up between the updates on the previous evenings inebriations and indiscretions.

If I have got this right Paul was suggesting that social media and advertising work quite well together in the service of a brand. Social media encourages people to like your brand and advertising encourages people to buy from your brand. So the combined effect is that people like to buy from your brand. While is quite a nice combined effect.

I love this model and think that it is applicable all over the place.

Here it is in chart form.

I have been working with this quite a bit recently. It works particularly well on something we call the New Value Mindset at S&S. This is the idea that the new sense of value that consumers have created since the beginning of the recession requires brands to be of value not just good value for money. If that is the case value claims in isolation (buy from us) are as problematic as communications that ignore value (like us). Better to deliver value claims in the context of the value you seek to be to customers.

Here is a brilliant example from Hyundai in the US.

It also works nicely to describe the difference between brand advertising (like us), direct response advertising (buy from us) and brand response advertising (like to buy from us). I have a longer post on just this subject that I am putting up in the next couple of days.

And finally, returning to the title of this post, it helps show why Sainsbury's is kicking seven types of shit out of Tesco at the moment. For those beyond the shores of Albion they are two UK supermarkets locked in mortal combat since the end of the pliocene.

Going into the recession the smart money would have been on Tesco winning since they had established a reputation for low prices and massive buying efficiences (£1 in every £8 spent in Britain is spent at Tesco). Tesco owned the 'buy from us' space and their first initiative was to position themselves as Britain's biggest discounter.

On the other hand Sainsbury's was the diletante of the supermarket category a brand that its customers loved but with no strong reputation for value, indeed quite the opposite. With lovely ads full of lovely food staring lovely celebrity chefs their communications were squarely in the 'like us' category.

Then a funny thing happened. While Tesco approached the recession with its neolithic discounting positioning - which upset its customers no end. Sainsbury's started showing that it was jsut as creative and resourceful as its customers with campaigns like 'love your leftovers' and 'feed your family for a fiver' all under and feeding the brand idea 'try something new today'. In a sense Sainsbury's has defined 'like to buy from us' best of all the UK supermarkets. Perhaps that's why Sainsbury's sales are up 7.8% since the beginning of the year while Tesco's are only up 4.3%.

Anyway its just a funny little chart. Maybe it will work for you. And once again thanks Paul for the inspiration.

Calling time on digital's cult of accountability

Image courtesy of Aussiegall

Occasionally I have the enormous pleasure of judging New Media Age’s Interactive Marketing and Advertising Awards. And a very splendid awards scheme it is too, with this year’s kings of the digital castle crowned in some style last month. I get invited to fill the ‘enthusiasm-over-experience’ role of digital-curious advertising outsider. This usually involves gobbing off in a cavalier fashion and then being slapped down by people that actually know what they are talking about.

However, there is one territory on which I feel on more solid ground, and that is campaign accountability. And in particular the ludicrous way in which the digital community generally sets about proving effectiveness, a not inconsiderable criteria, both in judging these awards and in the current business landscape.

Let’s be direct about this. Judging by many of the less successful entries, the standard measure for return on investment would appear to be the difference between the cost of the campaign and the cost of reaching the same number of people in more conventional media. That is not a return on investment, that is the sort of haphazard disregard for accurate accounting that precipitated the current global financial crisis.

Indeed, any effectiveness metric that does not tell you the incremental profit that your marketing activity generated for the business isn’t worth the paper it is written on. Not click through, not cost per impression, not cost per response, not page views, not dwell time, not fanciful measures of engagement. Incremental profit. And if that seems an extraordinarily difficult thing for most digital campaigns to demonstrate, I’m heartily sorry. But it doesn’t make it any less imperative the industry resolves this question, because it isn’t going away.

And I lay the blame fairly and squarely on digital’s cult of accountability. Accountability sounds like a thoroughly noble endeavour because it suggests an appropriate use of the client’s budget and an ability to show what happened to it. It is also a really handy stick with which to beat advertising agencies and their big production budgets and legendary levels of media wastage. However, accountability is a bottom up measure of success, and in truth it measures efficiency not effect. If digital agencies show client how wisely they spent the budget against the competition and versus last year, advertising agencies look at what happened to the business and then try and show how their activity contributed to that success. In other words they approach effectiveness from the top down, a fundamentally different world-view.

In fact it is precisely this cult of accountability that is getting in the way of the digital community progressing from clever marketing handymen to the architects of brand success. After all what Chief Executive is really the least bit interested in how responsibly any one has used their money? What they tend to be concerned with is whether their marketing is having an un-ambiguously positive effect on the growth and profitability of the business. In response to Lord Leverhulme, who cares if half your marketing budget is wasted if the other half is shifting shed loads of product?

So long as the digital community clings to its obsession with accountability over effectiveness it will remain in the unedifying position of creating engaging brand fluff on the one hand and highly measurable but largely pointless direct response advertising on the other. If that sounds like a future to you then fine but I’d suggest changing the fortunes of a client’s business is a finer ambition to hold. And that is going to need proper measurement.

Great ideas can come from anywhere, my arse

Image courtesy of Markus Nielsen

Image courtesy of Markus Nielsen

There are many terrible cliches that lurk like sewer rats in the daily effluent of the advertising industry. And much like sewer rats they are always close to the surface, wholly unpleasant and bloody difficult to eradicate.

By far the most pernicious and destructive is the now widely held belief that ‘ideas can come from anywhere’. What this annoying little platitude means is that anyone engaged in a project whether client or agency and regardless of their discipline may be the person that cracks the big idea.

So far so good and of course like all cliches it did have a use at one time. By the 1990’s above the line advertising agencies had become so overwhelmingly and unjustifiably arrogant that they effectively acted as a block on any form of collaboration or innovation. Whether within those agencies, between agency and client or between the different disciplines that were beginning to partner the advertising agency to deliver integrated campaigns.

Against this approach there was real mileage for those in the market that refused to indulge prima dona behaviour, that had more fluid and collaborative working practices and who were far more open to partnering other agencies. As a sales trick, suggesting that an idea can come from anywhere worked a treat, and indeed some clients more interested in the process of making work than the quality of the end result, lapped it up.

The trouble is that while there may be some truth in this belief - theoretically great ideas can come from anywhere, just as theoretically a sufficient number of monkeys equipped with typewriters will create works of great literary merit - it is a disaster for clients and agencies alike.

Maybe the odd idea can come from anywhere but from whom are breathtaking strategic, creative and executional ideas more likely to come? Who is more likely to be the architect of a ground breaking piece of strategic thinking? Who is more likely to find a creative expression that dramatises it in a way that has never been experienced before. And who is more likely to create an executional approach that mesmerises people? It could be anyone involved in the project but my money is on those people that do this every hour of everyday of their professional lives, people that instinctively know when something is verging on greatness or just a pile of tat.

And what on earth is the future for any company in the ideas business that pays its people and its rent by creating ideas no one else can possibly come close to, if they believe that actually its a piece of piss and anyone can do it. After all you don’t find architects running around suggesting that anyone can design a building or even that any other architect can design a building as well as they can. An agency might as well pack up shop and go home if it doesn’t have enough self respect to think that, although anyone might come up with an idea, no one is likely to come close to the God like genius that they can rustle up.

Clients value great ideas, they pay us for great ideas and they stay with agencies that consistently author great ideas. Any agency worth its salt will ensure that, while there may be a scintilla of truth in this hoary old cliche, the greatest ideas only come from them.

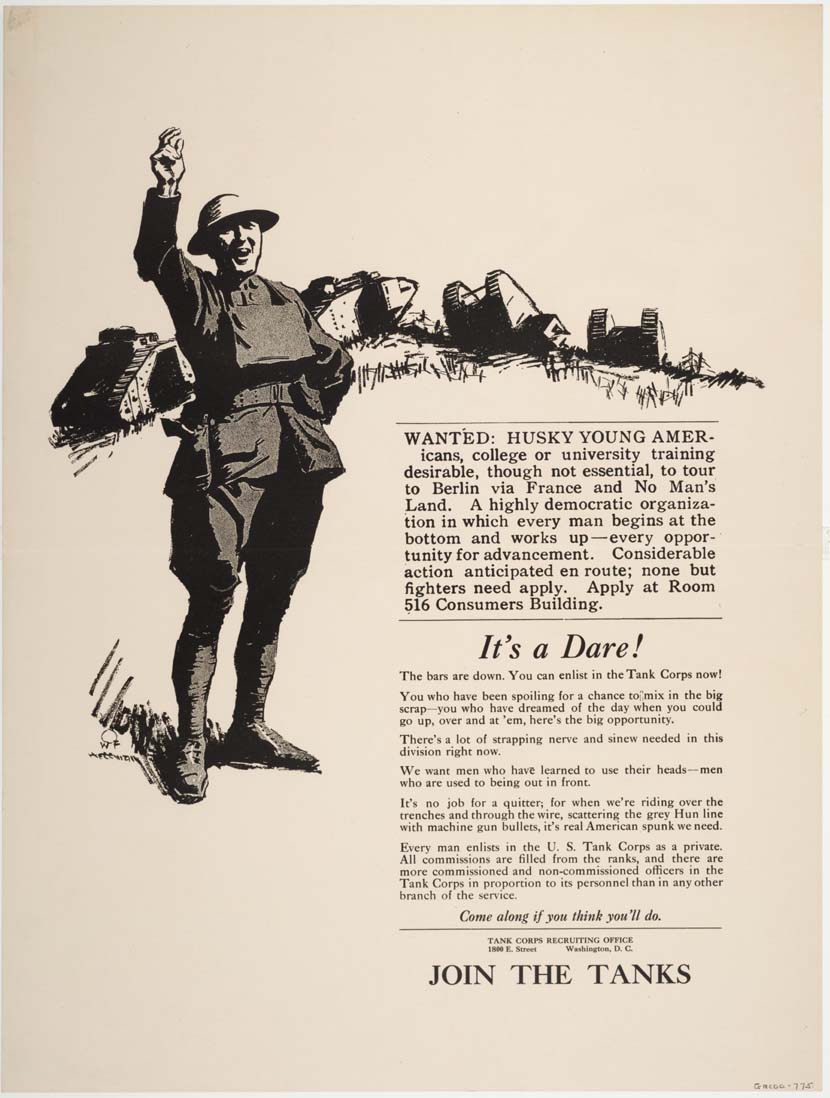

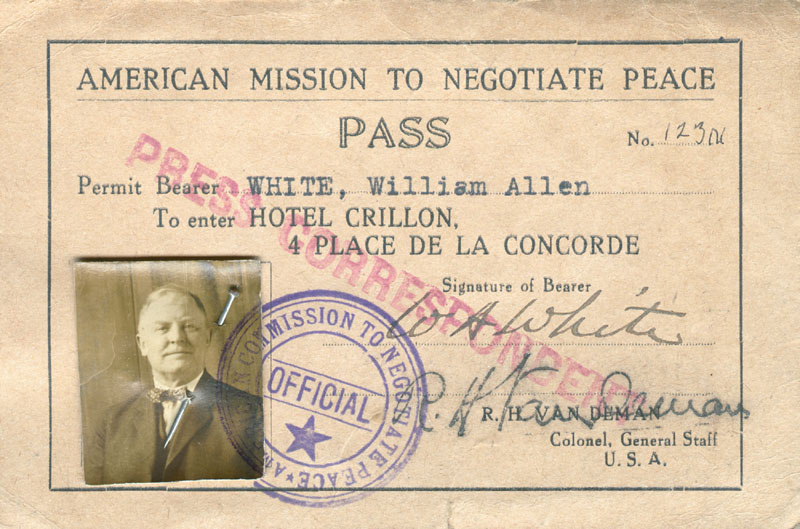

Welcome back America - we missed you

Telephone research must stop. Full stop.

Image courtesy of Old Telephones

Let's agree this now everyone. There are some things marketing and communications should steer well clear of and the telephone is one of them. So lets have no more telemarketing spam, lets have no more political parties ringing people up with an automated message and lets have no more telephone research.

Planners in advertising have a dark secret. While we spend a considerable amount of time commissioning and using quantitative research, we very rarely take part in it. Indeed, like most people that work in marketing, we are screened out from almost all market research. This rather arcane practice is based on the quaint idea that respondents should be ignorant of the research process thereby ensuring more accurate answers. This is similar to the way animals entering an abattoir are made unaware of their surroundings and so succumb to the experience placidly and without distress. Nice placid respondents are exactly what researchers like.

However, there is something deeply troubling when people asks others to undertake anything that they themselves never experience as customers. And so it is with research, where the end users of quantitative surveys often have no real idea of what it feels like to be a respondent, whether its because they decline to take part or are screened out from the interview in the opening seconds. The truth is that if we all had to go through the full horror of a thirty minute questionnaire, we would never let the length of our surveys get out of hand. If we ever had to experience the frustration of being asked to chose from a selection of banal pre-scripted answers that don’t reflect the way we actually feel, we would ask more open ended questions. And if we ever had to endure the imposition, irritation and imbecility of a telephone interview, we would never use telephone research again.

Telephone research, much like its evil twin, telemarketing is a perversion of both the noble role of the telephone and the honourable tradition of research. Not only must one question whether we should submit any fellow human being to the experience, but we should also be extremely dubious about the truthfulness of the results. Not least because finishing the damn thing, rather than recording accurate responses, often becomes the primary aim of interviewer and respondent alike. Thankfully, when it comes to research the telephone is an intermediate technology and one we no longer have to put up with.

While expensive face to face research remains the gold standard the internet is changing the way we acquire the information we all need to do our jobs, especially where budgets and timings are tight. Indeed there are often circumstances where the lack of moderator in online research improves its accuracy over face to face, particularly when it comes to political polling where people are often more honest if they are telling a machine. Online, respondents can chose the time they want to undertake the questionnaire they are participating in, they can consider the questions properly and they can consider the options for their answer properly. They can even come back to tricky questions or take a break from the survey altogether, ensuring that research is completed in a relaxed state of mind and without an impatient low wage interviewer breathing down their handset. While this may reduce the innocence of respondents it is actually possible that people will enjoy online research.

The internet continues to have a profound effect on the marketing business. However, at the same time as the noisy revolution that is taking place in the world of marketing communications the online survey is heralding a more profound but rather quieter revolution in the world of market research. We just need to make sure we take part in it from time to time so that it remains a positive experience for our customers, even if that means fibbing about our profession.

Problems wanted

Mad Men, a simpler time of real men, real problems and lots of sex on mid century design classics. Image courtesy of Slate.

Unfortunately much advertising is self indulgent nonsense that simply serves to waste the client’s money and the consumer’s time.

Sometimes, just sometimes this work is the product of precious and pretentious creative endevour that is brought into being simply to puff up the bloated ego of a creative director seeking to shove his make-weight agency up the award’s league tables.

However, more often than not the hollow stuff that troubles us most is not the product of some creative flight of fancy but the result of a hollow brief. And the blame for that must lie squarely at the feet of the client community, for being less than clear about the business problem they are trying to solve and less than clear about how advertising might be used to solve it.

You see advertising loves problems, the bigger and hairier the better. It is one of the reasons that some of the most creative and effective work in the market is done to Government briefs where there is often a proper problem and a need for a serious change in behaviour.

Ask any good creative agency what they crave most from clients and they will tell you that they want a clear and unambiguous problem to solve. In other words an objective. Inspirational client briefs are fantastic, especially if you can get a whiff of the spiritual brief that the client organisation really needs to deliver against. However, I’d sacrifice any amount of inspiration for a serious business objective every day of the week. Serious objectives like ‘slowing the loss of a retailer’s business to online competitors’, ‘increasing every transaction by £1.14’ or ‘become the clear number three in the market by taking share from the two dominant brands’. Not wooly nonsense like ‘increase brand awareness’ or ‘launch our product into the market’ and still less ‘make people love and engage with my brand’.

A desire for proper business problems partly explains the delight taken by the industry in the 1960’s advertising drama, Madmen. Sure there was a good dose of envy over a job which seemed to involve drinking vast quantities of whisky at all times of the day and having sex on top of mid-century design classics. However, its real success in adland was down to a wistful longing for a time when clients were actually clients. In other words the people that ran and had often founded the business being advertised and simply wanted to sell more of their products by any means necessary.

Of course the arrival of professional marketing departments has changed the relationships that agencies have with client organisations and the roles that they play for them. But it hasn’t change the need for clear business objectives.

And don’t for a moment think that the digital world is exempt from this criticism, because of an obsession with accountability. Interaction levels, click through rates and dwell times are important but they are not business objectives. The truth is if ad agencies have got it bad when it comes to getting proper problems to solve the digital community has got it far worse. All too often digital briefs are either at the terminally intermediate end of the spectrum, asking for an ever lower cost per response, or at the terminally fluffy end asking for lots of lovely brand engagement and little else.

This post originally appeared as a column in New Media Age.

As I please - Time to change tack on tobacco

The definition of irony. A British Red Cross ambulance paid for by the workers of the Bristol cigarette manufacturers WD & HO Wills 1914-18. Image courtesy of brizzle born and bred.

As a life long non-smoker and rabid anti-smoker, no one has appreciated and enjoyed the progressive decline in smokers’ freedoms than me.

A combination of punitive taxation and escalating restrictions on the places people can smoke, as well better education and more effective quitting programmes are taking their toll on the the hardcore of smokers out there.

And hurrah for that. Britain is an immeasurably more civilized place to live and work in now that you virtually never smell cigarette smoke.

However, even I have started to wonder whether it is time to change the focus of society’s efforts at stubbing out tobacco use. Even I have begun to wonder whether we need to lighten up on those that chose to light up and to put a halt to further restrictions in the freedom that smokers enjoy.

Most anti-drugs programme attack supply not just demand and yet the vast majority of the anti-smoking effort is directed against smokers rather than the makers of the stuff themselves. Increasingly this feels like a cop out.

In any functioning market economy there are a whole array of freedoms that commercial organisations should and do enjoy. The freedom to make the products and services that they see fit, the freedom to set their price, the freedom to promote them and the freedom to establish and use 'brands' to maximise the sales and profitability of those products or services.

They are freedoms in as much that society can limit them if commercial organisations, or the sectors to which they belong, transgress the rules and codes of that society. We might call this a withdrawal of priviledges, much as you might progressively withdraw freedoms from a trucculant teenager. And this is the place we should concentrate our efforts as a society, further withdrawal of the priviledges and commerical freedoms of the Tobacco industry.

It is true that we have already withdrawn the priviledge to promote tobacco in paid for media but the the next step in attacking the supply side of the battle against smoking has to be to remove the freedom to ‘brand’ their products and thus force the industry into a commodity market.

As we preach on a daily basis commodity markets are terribly unattractive place to be and particularly in this sector which is more dependent on its brands than its customers are on the weed.

Brands create sales and generate profits by making products more attractive to people than reason of price and availability would suggest. They are a means to establish and maintain market share and to command a premium over the competition for parity or near products. As we have so often said, brands are a business person’s best friend.

And that’s what makes it imperative that the right to use brand tools is removed from this sector. Commodity tobacco with products graded according to nicotine strength will remove what little wind is left in the sails and sales of Big Tobacco. After all attacking the supply side of the business is the real front line in the battle against smoking, not maximising the number of shivering people huddling outside the office having a desperate fag.

'As I please' was the name of George Orwell's regular column in Tribune during the Second World War

The work fights back

It is time to get unreasonable in support of truly great work. Image courtesy of Antar.Ellis

Returning to the world of advertising after a short break, I am reminded of the fundamental truth of our business. To paraphrase the advice given to Bill Clinton during the 1992 Presidential Campaign, it’s the work, stupid.

Great work delivers happy clients, new business and perky bottom lines. By and large if you focus obsessively on the quality of your creative output then everything else will fall into place. Of course by great work I mean proper nosebleed-altitude creativity not the usual lifeless fare that stinks of collaboration and compromise.

However, this mantra hasn’t been heard in London for a while outside one or two exceptional shops. For the best part of a decade creative quality has played second fiddle to a pleasant client experience and the immediate financial success of the agency.

The problem can be traced back to the point at which internet bubble burst at the turn of the decade and in the advertising recession that followed. The dot-com crash may have delivered a kick in the teeth to the fledgling digital industry but it had a far more lasting effect on the advertising business. It is no coincidence that dodgy digital entrepreneurs loaded with venture capital sought out precisely those agencies with the best creative reputations. In the short term it left our best shops with huge financial write-offs as bankrupt clients proved unable to pay their bills. In the longer term a far more cautious market destroyed the enthusiasm of clients to buy truly excellent creative work and the ambition of agencies to deliver it. Not only did established agencies go soft on the work, a rash of recession-fit start ups came to market built exclusively on client service platforms, and they cleaned up.

These were bad days for the strategically and creatively daring and, with one or two exceptions like BBH and Mother, these agencies had a tough time of it, many merging, shrinking or closing their doors. In particular creatively driven agencies found it far harder to win business than their more compliant and compromising rivals.

But here is the irony. Just as the economy looks rather less than robust the market might actually be swinging back in favour of braver work, with those agencies that kept the creative flame burning during the difficult times enjoying business success to match their impressive reels. And as the work fights back the benefit for the UK communications industry is that London has started to walk a little taller on the world’s creative stage. Cadbury’s Gorilla recently won the highest accolade possible at D&AD, the globe’s most prestigious creative awards and UK fingers are crossed for a robust performance at Cannes this week.

Moreover, the client community maybe starting to remember that better work delivers better results. Creativity has always been an important element in powerful communications but never before has the quality of the work had such a direct effect on the effectiveness of the budget, and the success of the brand. Because never before has the primary determinant of consumer reach been consumer engagement rather than simply ratings. Only a few weeks into the launch of the Gorilla ad, the number of people that had seen the film was almost double the number that Cadbury’s had actually paid to see it.

Agencies must capitalise on these changes in the communications market and in the client community’s apparent appetite for nosebleed-altitude creativity. And to do this they must be more unreasonable in their relationships with those clients, determined to deliver the best thinking and best work whatever it takes.

This post originally appeared as a column in New Media Age.

Are our start ups a let down?

Image courtesy of Fiat Luxe

The start up plays an almost mythical role in the world of advertising. Start ups are not simply an outlet for the professional and material ambitions of the best in the business, they are absolutely essential to the health and vitality of the industry. If advertising has managed to adapt to the changing business, consumer and communications landscape over the past century it has been largely because of its start-ups.

The concentration of talent and ambition in new agencies, coupled with their lack of moribund processes and crippling overheads means that they are able to

anticipate and quite often precipitate the changes that drive the business forward. Changes both to the process of creating advertising and the product itself, whether the media used or the selling techniques employed.

After all it was start up agencies like Collett Dickenson Pearce that in the 1960s first got their heads around how to use the fledgling medium of commercial television. While successive start ups from Saatchi & Saatchi in the 1970’s to Bartle Bogle Hegarty in the 1980’s and Mother in the 1990’s all used their success to lead the advertising business in new directions. And in doing so frustrated those that repeatedly predicted advertising’s demise.

Of course, while the attractiveness of younger, more agile agencies takes its toll on more established shops and every generation sees many of these fall by the wayside, unable to compete with the new offerings, many others survive and prosper. And they do so precisely because their deep pockets and generous owners buy back the talent, energy and new practices that the start ups have pioneered. And so the young turks return to the fold and in doing so change the agencies they originally left with far greater success than if they had stayed on.

Recently, however, something has gone wrong. In the last decade there has been no let up in the number of new advertising agencies, yet those born in this period have conspicuously failed to maintain the pace of change upon which the survival of the business is so dependent. This has been cataclysmic in London which, starved of start ups with new ideas, has become a shadow of its former, world conquering, self. If you had said to your average adman in the 1990s that the agencies that we would most respect a decade later, would be almost exclusively American they would have laughed into their cinnamon lattes. Not since the 1950s has London adland doffed its cap to the US with such awe struck admiration.

For far too long the hallmarks of the start up - fearless audacity, challenging thinking and world beating creativity - have been rare qualities in the UK’s young agencies. And this has to change if London is to restore its fortunes as a centre of advertising excellence.

Maybe the latest crop of start ups will be different. 2008 has begun with a flurry of agency births, the most notable being Adam + Eve and AnalogFolk, both breakaways from large network agencies. Refreshingly they do seem to promise new thinking and new ways of working, and interestingly both have been quick to bring in talent from outside orthodox advertising agencies, all of which bodes well.

We have to hope that this year’s start ups can deliver real change where their immediate predecessors have not. Because if you want to point your finger at anyone for the advertising industry’s failure to adapt don’t do so at the established agencies - this was never their role - point it at the last decade’s start ups that have delivered so much cash to their founders but so little progress to the business.

This post originally appeared as a column in New Media Age.

Loyalty my arse

Image courtesy of Simon Lord

Every morning as I meander to work in Charlotte Street I fortify myself for the day ahead at the Caffe Nero on Tottenham Court Road.

And every morning as I hand over the cash they parrot the same old question ‘do you have a loyalty card’. And every morning I mumble a 'no' and move onto the next question which is about muffins or other items from the pastry selection.

Last week I ventured a more adventurous answer to their inanities, ‘you keep on making good coffee I stay loyal, you stop making good coffee I sod off’ (naturally this endeared me to the staff no end).

And that of course is the truth about loyalty.

Brand Loyalty is based on brand delivery, whether tangiable (great product performance) or intangiable (heaps of lovely identity value), it is not based on silly little loyalty card schemes or silly big loyalty card schemes for that matter. These are more accurately known as bribes and in a fairer world would be seen as a petty form of corruption. ‘Yeah I know that the product is shit, we are ripping you off and the service stinks but heres a bit of plastic that means for every half a million quid you spend in our store we will give you a half sucked polo mint and a bit of old string. Oh and occasionally we will send you a really poorly targeted bit of eCRM that will irritate the hell out of you but at least it won’t fill up your recycling bin like the other crap we send you. enjoy’.

OK, maybe I am a bit extreme as I refuse to take part in any reward programme as a matter of principle. But I am not content to simply pass up a free cup off coffee for every nine I buy, I really would like to see the whole stinking edifice of the loyalty business brought to its knees. For the simple reason that it perverts the behaviour of businesses.

For as long as organisations are focused on bribing their customers to continue purchasing from them they are not focused sufficiently on the real source of loyalty and that is providing a product that people find irresistible and refuse to substitute. And more than that, a product that people actively advocate in a slightly scary thousand-yard-stare kind of way.

Indeed I wonder how many brands or businesses that have these wonderful loyalty programmes actually have positive Net Promoter Scores - that’s where the number of customers that score the business 9 or 10 out of 10 for likelihood to recommend to a friend out-weigh the number that score the business 1 to 6 out of 10. With Net Promoter Scores you bin the 7s, and 8s as having a passive relationship with the brand and thus of no use to to man nor beast. Moreover, I wonder whether any of the brands that are really successful in creating strong advocacy have to bother with the bribes at all given their loyalty is based on far more fundamental relationships. Can you imagine an Apple Loyalty Programme?

So join me in my crusade against the business bribe, demand loyalty from brands rather than offering up yours for the price of a coffee and repeat after me ‘Loyalty my arse’, or as they might say in Cupertino if they weren’t so Californian and therefore allergic to bad language, ‘Loyalty my ass’.

The death of serendipity

Serendipity is not only a beautiful word it is a very beautiful thing.

One of the great delights of life, serendipity ploughs a furrow between co-incidence on the one hand and fate on the other while being part of neither.

But I’m rather afraid that it is progressively disappearing from our lives, collateral damage in the quest to deliver and receive ever more relevant entertainment and communications.

The word itself was first coined by Horace Walpole in 1754 and is derived from an old Persian fairy tale called The Three Princes of Serendip. In this fairy tale the three Princes are constantly making discoveries and coming across stuff they never set out to find.

And that’s what serendipity is all about, the effect of accidentally discovering something fortunate especially when looking for something else altogether.

One of the greatest moments of serendipity in human history was of course the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming who had failed to disinfect cultures of bacteria before popping off on his hols. On his return he found that the mould that had subsequently developed had killed off all the bacteria.

Now, few of us will have the pleasure of discovering a life saving solution to bacterial infection but we do enjoy the pleasure of serendipitous discovery all the time. It is when we get to do or experience something that we didn’t know we would enjoy. Maybe its a shop we discover hidden down a backstreet that we take because of roadworks on our usual route, or a fascinating article in a magazine left in a waiting room we thumb through out of sheer boredom, a website we come across while hyperlinking through cyberspace, or a sandwich bar you try because it is recommended by someone you meet in a lift carrying their lunch. You know that kind of thing.

In our world this kind of serendipity has been one of the very few upsides of our historically restricted choice of entertainment.

We discovered music we didn’t know we liked because there was so little choice of radio to listen to. We saw TV programmes that we didn’t know we liked because that was what we had available to watch at the time we were available to watch. Who knows we may even have bought something because of an ad in a programme we were watching by accident and that wasn’t ‘targeted’ at us.

More than that we were prepared to let things grown on us because whether listening to the radio or watching the TV, or enjoying any other form of entertainment it wasn’t like there was much of an alternative. Someone recently described this to me as the 15 minute rule - we used to say when forced to watch something we wouldn’t have normally bothered with “I’ll give it fifteen minutes and if its shit I’ll watch something else instead”. Not only did we get exposed to things that we didn’t know that we liked but we were also ‘forced’ to give new stuff a chance.

And this process of accidental but serendipitous discovery enriched our lives and in a small way allowed us to grow and change in unexpected and unpredictable ways.

But serendipity of this sort is disappearing precisely because of the technologies and targeting that we believe is making our lives easier and more fulfilling. This is particularly marked by the culture of ‘on demand’, whether the immediate gratification of our entertainment desires is served by PVR’s, i-players, listen again services, search engines, recommendation engines to and I guess even specialist TV channels and radio stations.

Heaven forbid that we might actually experience something these days that we didn’t already know that we liked!

I think that the key challenge in entertainment in the near future will not be the delivery of enough of a content long tail to make on demand services work for people (critical for the burgeoning on demand TV services), nor the navigation systems that will help unite people with the stuff they already know that they like. But tools that reintroduce serendipity into our entertainment lives, tools that help us discover the stuff we never knew we were interested in.

Incidentally, I believe it is increasingly the role that the generalist offerings of the BBC in the UK are beginning to play, not least TV channels like BBC4 which might easily be repositioned as the serendipity channel.

And there may be a parallel in targeting or rather the lack of it. Modern marketing believes that the more that you can relevantly target communications the better, for advertiser and audience alike. Now let’s leave aside the crass assumptions that most targeting is based on and that simply serve to increase irritation at the breathtaking arrogance and intrusiveness of so called personalised communication, and simply dwell on what we used to call wastage.

In advertising we have always had a sneaky suspicion that a bit of wastage was a good thing, just incase we had got our targeting wrong. Well might I suggest that we re-define this not as wastage but as the part of the budget left for serendipity. That’s the bit of money that brands should spend taking to people that neither the brand nor they themselves know are in the market for the product or service yet.

So whether your interest is in finding new customers or finding new music. Leave some time and technology to dedicate to the endangered delight of serendipity.

I don't want you to be my friend on facebook

When I say I don't want you to be my friend I don't mean you, dear readers.

I mean brands.

Even lovely Innocent thinks I might want to chum up to them on the social network de jour and I don't, I'm sorry I don't.

People may be brands but brands are by and large not people.

And yet marketers consistently get confused about this. I put it down to too many brand personification exercises in those ghastly all day "off site" brainstorms that peope in marketing love so much.

And I guess to the idea of brand personality.

Brand's do have personalities and I spend a lot of time thinking about powerful personalities for organisational brands that capture the specialness of the place while legislating for it to be delivered in every expression of that brand.

But just because a brand has a personality doesn't make it a person.

And I want my relationships to be with people not businesses. Sure that can be the people in those businesses but not the business as a whole.

It's why I refuse to join "loyalty" programmes regardless of how fanatical I am about the brand or the bribe that they are offering to hand over my loyalty. I am loyal to people not to brands.

And this is why I think corporate blogging is such a bad idea. People in organisations can blog and people can blog on behalf of organisations (Visit Wales is building a series of blogs written by people in Wales about their experiences and lives for instance), but brands can't blog - who'd be interested?

And I guess that's what makes me so angry about the way brands are gatecrashing social media - media that we built to create communities and conversations with each other, not with packaged goods.

Guys just because you can doesn't mean you should.

At least in traditional media there is a basic level of respect that keeps the communication inside ad breaks and clearly demarcated from the content. But on the internet brands brands wander around like really irritating guests at a party, intent on looking in every room, having a butchers in your wadrobe and trying on your pants.

Online there are no no go areas at all, and guess what happens once a brand has had its fun? It sods off to the next big thing which, in the words of the fast show, 'this week is mainly Facebook'. Witness the speed with which brands got into and out of Second Life faster than a particulaly nasty bug gets through your digestive system.

And this behaviour is driven by unscrupulous brand advisers that treat the internet like the big trawler fleets treated the oceans for much of the twentieth century - a place where you can do what the fuck you like, cause any amount of damage and never suffer the consequences in your lifetime.

Even those of us that eat, sleep and drink brands acknowledge that there are places where brands aren't welcome. And I am increasinglly of the opinion that social media is one of those places.

There are many brands which I am absolutely fanatical about but I don't want to be their friend on facebook because, and I hate to break this to you, brands are not people.

Emotion is the greatest form of interaction

I recently had the pleasure of judging two sets of industry accolades.

The first was the Account Planning Group’s Creative Strategy awards and the second, New Media Age's Interactive Marketing and Advertising Awards, at which I was the above the line cuckoo in the digital nest.

Now, we all have our own view of awards and their importance or otherwise to the business we work in. However, I never fail to find them hugely instructive as a barometer for the way an industry is developing and the ebb and flow of ideas and practices.

For instance, despite all the talk of digital shops getting planning and planners getting digital there is very little cross over between the entries at these two events. The APG still draws the majority of its entries (with one or two very notable exceptions) from advertising agencies and the IMAA from digital and media agencies.

I want, however, to expand on another and far more subtle difference with broader learning for the world of digital planning and creativity.

The fact is that I didn’t cry once while judging the IMAA. Over the week of shortlisting and day of judging I laughed, played, engaged, gapped in awe and doffed my technological cap. But not once did the tears well up in my eyes or the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end.

Not so the APG awards. On more than one occasion I had to fight back my tears and swallow the lump in my throat in order to get on with the serious business of dolling out gongs. Most notable in the waterworks department was the Nike Air Max campaign that honours moments of devastating sporting failure to the strains of a dying Johnny Cash singing his rendition of ‘hurt’. It gets me every time.

However, this isn’t just a plea for more emotional digital work, although I think this development is inevitable as the discipline’s creative confidence and competence increases and the emotional bandwidth of the tools available increases. After all that is what happened in traditional advertising once the novelty of a brand going on TV ceased to be reason enough to go and buy it.

This is actually a plea to refine our definition of interactivity. As an industry we have a very one dimensional view of what constitutes an interaction between people and a brand and it almost always involves pushing some kind of button, whether on a remote control or a mouse. It’s a very physical thing.

This utterly disregards the fact that the most powerful form of interaction a brand can solicit is exactly the reaction the Nike work creates – emotion. This is a response you can’t measure with clicks or dwell time but in raised pulses, dilated pupils and the crackling sound of synapses firing.

That’s why we love Gorilla, Balls, Evolution and the other real stars of today’s interactive advertising landscape – they generate powerful emotional responses. And the more we learn about the way campaigns work the more we understand that emotional persuasion trumps rational persuasion every time.

So why is the simplest form of human interactivity somehow seen as illegitimate in the armoury of the interactive marketer? Why can’t the technology that we all delight in be used to bring emotion to the brand relationship not just the relationship between users? And why is novelty prized so highly over other, more subtly powerful forms of persuasion?

It is high time that we recognised that emotion is the highest form of interaction and prepared for the judging the next digital awards by stocking up on the Kleenex.

A version of this article originallya appeared in New Media Age.

We won't make that mistake again

Here is a naïve hope for the future.

That our personal and intimate involvement in the social media revolution will stop us making the mistakes of the past when it comes to applying the many and varied techniques, tools and applications of web 2.0 and beyond to our clients' brands.

One of the chief problems that faces marketing communications, of any discipline is that its practitioners are rarely on the receiving end of the material they produce. As a result they tend to lack a personal sense of what a piece of communication feels like and the context in which it appears. Much like the architects of mid century social housing.

One obviously assumes it’s the case with out-bound telemarketers otherwise why don’t they all go and jump off a cliff of shame somewhere?

It certainly seems the case with DM. Its practitioners are rather isolated from the experience of being on the receiving end of their activities. Sure they get the seed mailings but its all rather hypothetical. And what is more their work (being so direct) is rarely held up to public scrutiny. No doubt some bright spark at the Carphone Warehouse thought that sending me a mailing with 7 ‘personalised’ uses of my name was a brilliant wheeze when they could never know whether that was an appropriate approach (it wasn’t, it was crass) or that some arse had entered my name wrongly into their database. CRM fantasies always seem better in the boardroom than they do on the doormat.

It is less the case with moving image advertising since most people that make ads for TV, consume their own advertising in the breaks they themselves watch. Maybe this is why daytime TV advertising is so bad – the people that make it are at work scrutinising the cost per response, not watching the breaks and feeling the pain.

Bizarrely it should never have been the case with old school interruptive online advertising. Surely the people making all those pop ups were aware of how much we disliked them since they were very personally involved in the online experience of the time. I guess the lure of the fast buck led to much turning of blind eyes in the pre web 2.0 world.

So here is the naïve hope.

That because we are all intimately involved on a very personal basis with the social media revolution – writing blogs, reading blogs, Twittering, joining Face book groups, playing MMORGs and the like that we will think twice about the way that we encourage brands to use these tools, applications, techniques and worlds. That we are enthusiastic when the approach is appropriate and cautious when our clinets brands or activities would be unwelcome.

Because we ourselves actually understand the context of communication, not from research, but from personal experience.

In defence of the brand monologue

The word monologue has acquired a rather pejorative meaning in the world of marketing.

Monologue, where the brand addresses an audience and puts forward its point of view (as happens in traditional one to many advertising), is seen to be out of step with the idea that markets are conversations and depend on a dialogue of equals between brands and customers.

More than that, brand monologues are assumed to narcissistic, self referential, and disrespectful of empowered consumers that don’t have to or want to take that kind of shit from anyone least of all businesses.

Well I want to make a stand for brand monologues – right here and right now. Indeed I am going to insist that great dialogues start with a passionate monologue.

It is a mistake to think of the monologue as boorish and self congratulatory, at best it is precisely the opposite.

The greatest speeches of our time and throughout history are of course monologues – inspirational and passionate statements about the speaker’s beliefs, and clear exhortations to action on the part of the listener.

Speeches so powerful and motivating that they are often know by their most famous passage – “we will fight them on the beaches”, “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself”, “ask not what you country can do for you”, “the wind of change”, “an ideal for which I am prepared to die”.

These oratorical masterpieces are all monologues. They are monologues that began a million conversations and changed our very history.

I am not suggesting for a moment that brand communications can be equated with the words of the greatest statesmen and women. But merely to make the point that great monologue, from wherever it comes, is a catalyst for conversations that are all the richer for it.

Monologues provoke, inspire, move, motivate and set agendas. They are the essential beginnings for something else.

So I don’t want to see fewer brand monologues as the age of conversation progresses; I want to see more and better brand monologues.

You see every brand has an obligation to communicate why they exist, what it is they believe and what role they seek to play in our lives. That few do is an indictment of the quality of marketing in those organisations and the lack of willingness or talent to make these things clear to us.

Too many marketers in clients and agencies are prepared to accept ‘commodity market conditions’ and ‘low interest categories’ as excuses for inaction rather than a warning sign that something must be done, and done fast.

The job of marketing is to elevate a brand to the point where consumers are passionate about it and the business escapes the eternal downward force of the commodity market place. Not to piss around inventing new promotions, creating hilarious advertisements or leaping head first into social media the brand and agency has not the first clue about.

A categorical statement of the point of a business, brand or communication delivered from that organisation to the consumer – a monologue in other words - is not just to be welcomed rather than shunned as an anachronistic relict of a brandscape long gone. It is essential.

If a brand is prepared to do that then I am prepared to engage with it and enter into a dialogue about our futures together. If not (and I refer to the mobile phone network debate we had recently) then I’m not prepared to enter into any kind of conversation with them.

All dialogue and no monologue makes Jack an extremely dull brand.

If the work is wrong, speak now or forever hold your peace

I was talking to an eminent chap from the media world recently.

I was giving him my impression of media planners that was almost completely incorrect. He was giving me his impression of what we used to call account planners.

And I was rather shocked at what he said.

As far as he was concerned the problem with the planners he came across from the creative side of the fence was their myopic and ad-centric remit.

It seemed that him that these planners were locked into the old fashioned planning cycle of evaluation, brief writing, creative development and evaluation again.

In particular he accused them of seeming to have one primary purpose in his experience. To prove that the creative solution that had been presented to the client was the right one – whether it was good, bad or indifferent.

In other words the planners he met had abdicated their responsibility for ensuring that the work works and were paid to be the intellectual bitches of the creative director and a cadre of account people desperate to get work through at any cost.

In my shock I assured him that these sorts of shady practices had been consigned to the dustbin, as likely to take place as bear baiting, the ducking of witches and the evisceration of convicted criminals.

But there ain’t no smoke without fire plannerkind.

Our job is not to tow the agency line at any cost regardless of whether we believe in the line being drawn. Our job is not to do groups behind the client’s back in the desperate hope that they will throw a lifeline to un-bought work. Our job is to do nothing that will compromise the effectiveness of the work.

Account handlers get fired if the work doesn’t happen, creatives get fired if the work is no good and planners get fired (or should get fired) if the work doesn’t work. It is as simple as that.

Clearly if you have work that is staggeringly good, makes you unutterably excited and that you simply know (whether from your gut or your research) will get the tills ringing faster than the polar ice caps are melting then put every fibre of your being into getting it made and out in front of the people that matter. And give the craft disiplines the space and freedom to make the work magical.

But…

If you think the work isn’t up to scratch at anystage of the process it is your professional duty to represent that point of view to the agency and the client alike. And to do something about it.

Whatever stage of production the work is in.

If you think the rough cut isn’t right, that there needs to be a price, that the work is poorly branded, that the grade is wrong, the photographer’s book is inappropriate for the audience or there needs to be a voice over rather than supers then it is down to you to sort it out.

By god you’d better be right of course.

But if you are right and you sit on your hands, the work doesn’t work, the account gets reviewed, and you lose the business, guess who should be getting their marching orders ahead of everyone else?

Of course I’m sure this never happens these days and planners out there are all building brilliant brand strategies, helping to create astonishing executional solutions and fine tuning the work to within an inch of its life.

But on the off chance the media guy was right.

Cut it out.

You are damaging your personal and professional credibility and the discipline of planning in your actions.

Why we still need the Carphone Warehouse

I have just had to get myself a mobile phone contract.

I guess that dates me since mobiles/cellphones happened after I started work and so I have never had one of my own.

So as a matter of course I went to the Carphone Warehouse (The UK's largest cellphone intermediary).

Needless to say it was a pretty grim experience.

It was the Camden Town store in London. They have just moved into it and it is a really rather lovely shop - minimal, reserved and smart.

But as we all know nice store environments are easy to deliver, good service less so.

Not only was it difficult to engage any of the staff in an interaction that might actually lead to a sale (they only condescended to talk to me on my third visit) but information was incorrect (necessitating a fourth visit) and in the end they gave up on helping me transfer my old mobile number to the new network and left me to my own devices.

So like I say, not a very pleasant experience and hopefully one I will never have to repeat.

But what the hell was I doing there in the first place?

Flanking the shop on Camden High Street are stand alone stores for all the major UK networks, all of whom spend vast amounts of money promoting their so called 'brands', and who in theory should have done away with the need for an intermediary like The Carphone Warehouse years ago.

Sure, there was a time when the networks had patchy coverage, the industry was immature and consumers like me lacked confidence so an intermediary was just what we all needed - an honest broker in a sea of consumer confusion and network flannel.

But what possible role might it play now, when we are savvy and the cowboys have hung up their spurs?

Surely my inclination should have been to cut out the middle-man and go straight to the brand I trusted most, had a special affinity for, imparted the most identity value to me or just had the best deals. The Carphone Warehouse should be as anachronistic a business as its name suggests.

And I think that the answer lies in the fact that the Carphone Warehouse is at least a brand unlike the network operators and despite their vast marketing budgets.

Orange may have been a brand ten years but it is now a pale and lifeless pastiche of its former self. I remember it being the only network brand I considered when I got a mobile for my partner in the mid-90s, how times have changed.

O2 is little more than an identity system - ubiquitous, pretty and flexible but meaningless.

Virgin (which I opted for) has the stench of your un-cool uncle that is trying to get with the kids.

You couldn't wish for a more one dimensional brand than T-Mobile which doesn't even have the advantage of a pretty logo.

And while Vodafone has a nice brand strategy up its sleeves (in the ‘power of now’ idea) it has done very little to create real consumer affection.

Oh yes and there is 3, wayward 3, I think I'd be more likely to entrust my children to the local parish priest for the weekend than give them any money.

Trapped in some branding time warp the best that these organisations can muster is the relatively Neanderthal achievement of each owning a colour

Sure I'm aware of the event sponsorship that each of the networks indulgence themselves in as an aid to corporate masterbation, and I find the ads for Orange in UK cinemas really very funny. But if you think that putting your name on the chests of a Formula One team is going to make a difference to my network choice you evidently think it is 1907 not 2007.

As a result I couldn't have cared less which network I joined and more than that do not feel that I have any relationship with the one that I did (much to the annoyance of the carefully un-scripted call centre staff who all want to be my best friend).

And I'd suggest the churn levels in the industry indicate most consumers don't care which operator they are with either. In 2005 Vodafone's annual churn in the UK was nearly 30%.

These are not brands in the sense that you and I would understand them - they are businesses with pantone references.

That's why we still need the Carphone Warehouse and other intermediaries like it. Because in categories where the principle players can't be arsed to differentiate themselves an intermediary, particularly one that has mustered a bit of heritage, latent affection and employed the services of an anthropomorphic telephone can make a killing.

In the land of the blind the one eyed brand is king.

Don't blame it on the creatives

It has of late become awfully fashionable to lay the many and varied problems of the advertising industry at the feet of creatives.

They are accused of many things including introspection, arrogance, irrelevance and rank stupidity.

And of all their crimes the ultimate is that they simply ‘don’t get it’.

Neither planners nor suits are collectively damned in this way.

Indeed in some circles, particularly the blogosphere, the ridicule meted out to above-the-line creatives borders on a kind of blood sport like hare coursing or bear baiting. In particular it is practiced by members of the new marketing mafia who never made it in proper advertising and consequently have a massive chip on their shoulders.

Well I’m getting a little fed up of this.

It is true that the caricature of the above-the-line-creative as preening popinjay, more interested in the podium at the Grosvenor than the commercial success of their clients has a basis in truth.

Many agencies do run creative departments that are cushioned and isolated from the changing world around us with the effect that the creative teams inside become institutionalised into a particular way of behaving. In particular some agencies still insist on segregating the creatives from the rest of the company on separate floors like oriental eunuchs might have been kept away from the rest of Court.

Many agencies do still use creative awards as the basis for rewarding their teams, so that winning gongs judged by people outside the agency with their own standards and agendas is the only way to get ahead in this business. The worst excess of this is of course the placement of an ‘award’ winning ad in marginal and often agency-bought media or editing the agency’s ‘cut’ of an ad for showreel purposes.

Many teams do have television touretts, capable of the rhetoric of ‘big ideas’ but not the ability to envisage them in anything other than script form.

Most teams still have a bizarre obsession with ads having ‘ideas’ despite the fact that they have no idea why these might or might not be important or work.

And many teams and creative directors still use moribund concepts like talkability and cut through to justify their work to the agency and client alike.

However, all this reprehensible behaviour is merely the result of a bunch of people trying to do to the best of their ability something that they have been trained to do from the outset of their careers.

If that is no longer what we want from them then we have to take some responsibility for changing the situation rather than simply making fun of the ‘old-school’ creative team, whether online or in the pub.

Many years ago advertising had a very simple task. To tell alot of people why a particular product or service was brilliant. Advertising amplified something good about the brand and ensured that enough people knew enough about it to make a purchase decision.

But things started to get complicated when the era of mass production and over supply meant that many identical products or services were now competing for our attention.